by Aurore Spiers, University of Chicago

The JoAnn Elam Collection (1967-1990) at Chicago Film Archives (CFA) is one of the 58 archival projects receiving generous support from the Woman Behind the Camera. It consists of approximately 735 film, video, and audio elements and some paper material, which JoAnn Elam’s husband Joe Hendrix donated in 2011. Since then, CFA has inventoried, digitized, and catalogued some of this material, giving the public unprecedented online access to the filmmaker’s work.

In addition to Elam’s best known films, such as Rape (1975) and Lie Back and Enjoy It (1982), the collection includes many short films, home movies, and unedited footage for Everyday People (1979-1990) and other unfinished projects. It also features medical films by Elam’s father, James O. Elam, M.D., and home movies by Joe Hendrix. This heterogeneity together with the diversity of formats (8mm, Super 8mm, video, 16mm, and audio tapes) and the scarcity of remaining information about some of the material make the JoAnn Elam Collection an archival challenge, one that I was excited to learn about and work on as CFA’s research intern this summer.

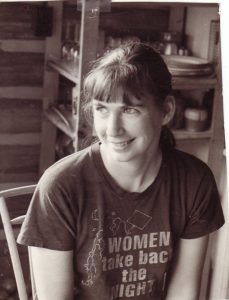

JoAnn Elam in the late 1970s.

JoAnn Elam was born in Boston in 1949 to James O. Elam, a physician who specialized in anesthesiology, and Elinor Foster Elam, an active member of the League of Women Voters in Chicago. She grew up in various places in New York State and Missouri, as the Elam family moved around for her father’s work. In 1966, she moved to Yellow Springs, OH, where she attended Antioch College and met her first husband, the experimental filmmaker Bill Brand. He and Elam participated in the local, vibrant artistic community of Yellow Springs and Elam’s first finished film, 3 Goats and a Gruff (date unknown), was supposedly shot there in the late 1960s.

In the early 1970s, Elam and Brand moved to Chicago and Brand enrolled in the MFA program at the School of the Art Institute, where Elam sat in on Stan Brakhage’s lectures. In 1973, Elam, Brand, Warner Wada, and Dan O’Chiva formed Filmgroup, later renamed Chicago Filmmakers, which had the mission to showcase their work and the work of other young experimental filmmakers during screenings at the N.A.M.E. Gallery downtown. Chicago Filmmakers remains a staple of independent filmmaking today. Elam’s group of friends at the time, nicknamed the “Rhinos” or the “Rhino group,” also included B. Ruby Rich, Linda Williams, Julia Lesage and Chuck Kleinhans from Jump Cut, and many other filmmakers and scholars. Although Elam did not achieve the same level of recognition as some of the members of the “Rhino group” and Chicago Filmmakers, similar cinematic experiments characterize most of her finished and unfinished works from the JoAnn Elam Collection, such as Filmabuse (ca. 1975), Disabuse (date unknown), and Sprockets (ca. 1976).

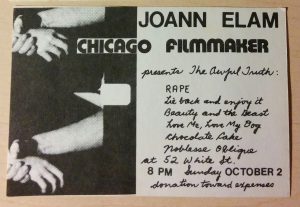

Promotional material for “JoAnn Elam Chicago Filmmaker,” New York City, October 2, 1983. Courtesy of Susan Elam.

Equally influential for Elam was her involvement in the labor movement of the 1970s and 1980s. In 1973, the same year that she co-founded Filmgroup, Elam started working as a letter carrier for the United States Post Office in Logan Square in Chicago. At least three times between 1978 and 1982, Elam served as one of Chicago’s union delegates to the National Association of Letter Carriers biennial convention. Several titles from the JoAnn Elam Collection document this moment in the history of the postal workers’ unions, when tense negotiations with the Post Office administration led to many protests, strikes, and, in some cases, victories for the workers. In Everyday People, which was one of Elam’s most ambitious projects that unfortunately remained unfinished before she died in 2009, she explores the letter carriers’ role in the communities they serve, their difficult work conditions, and the racism and sexism they face every day. The film’s experimental documentary form reveals the ways in which both her experience as a postal worker and her ties to Chicago’s experimental film community informed her film practices throughout her life.

Knowing about these aspects of Elam’s life has been essential to my understanding of the JoAnn Elam Collection. One of the challenges I still encountered was to determine the production locations and dates and to identify the people in Elam’s films. When none of Elam’s notes remained, the help I received from her sister, Susan Elam, and her close friend, Chuck Kleinhans, proved invaluable. In some cases, the personal photographs and memories of Elam they shared with me illuminated her methods as an experimental filmmaker. For instance, in Collards Garden 1985 (1985), Elam appears on screen planting collard sprouts and then picking fully grown collard greens in a time-lapse fashion. Even if Hendrix stands behind the camera, Kleinhans has described him as Elam’s “helper” responding to her directions and whose participation in her projects should not weaken her artistic authority.

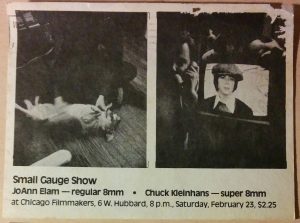

Promotional material for the “Small Gauge Show” with films by JoAnn Elam and Chuck Kleinhans, Chicago, February 23, 1980. Courtesy of Susan Elam.

“Small Gauge Manifesto” (1980), which Elam wrote with Kleinhans as a pamphlet distributed at Chicago Filmmakers, also gives us some insight into Elam’s preferred film formats (regular 8 and Super 8), editing practice, and viewing conditions. With small gauge film, Elam and Kleinhans argued, “filming can be flexible and spontaneous. Because the equipment is light and unobtrusive, the filming relationship can be immediate and personal. The appropriate viewing situation is a small space with a small number of people. (…) The filming and viewing events can be considered as part of the editing process. Editing decisions can be made before, during, and after filming and can incorporate feedback from an audience.” The conclusion of their short manifesto, “small gauge film is not larger than life, it’s part of life,” describes Elam’s consuming devotion to filmmaking well. As she was often bringing her camera along, filmmaking was always part of her life.

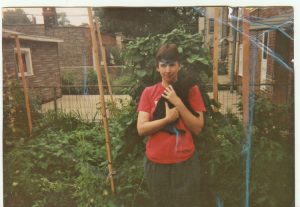

JoAnn Elam in her garden in Chicago in the 1980s. Courtesy of Chuck Kleinhans.

Eager to experiment with conventional filmmaking and editing practices, Elam often filmed her garden, the many places she and Hendrix travelled to, the union meetings she participated in, the people gathered around her at barbecues and family reunions, strangers on the street, her cats and dogs at home, her plants on the windowsill, everyday activities like riding in a car or on the subway, and special occasions using defamiliarizing techniques. Some of the films she made in Monterey, MA, in the early 1980s, such as Monterey Goats (1981) and Monterey Maple Farm 81 (1981), exemplify her fascination for natural beauty and farm labor, which the frequent use of superimpositions, fast-paced editing, and disorienting camera movements make all the more intriguing. Even a short film like Sailboat (ca. 1976), in which a sailboat on Lake Michigan gets closer and then further away within seconds through framing and editing, tests the medium’s potential to reinvent both reality and itself.

In many instances, Elam’s experiments helped her search for new, empowering ways to film women, not as images produced by and for the patriarchal society, but as voices rising against it. Rape, Chocolate Cake (ca. 1973), Lie Back and Enjoy It, and Daytime Television (date unknown) are compelling examples of Elam’s reflection on violence against women, traditional ideals of femininity, and the representation of women in mainstream media.

As one of the few women working behind the camera in the 1970s and 1980s, Elam’s contribution to American experimental filmmaking was original and provocative, making her absence from most film histories all the more regrettable. The work of Chicago Film Archives on the JoAnn Elam Collection remedies this oversight and makes it possible for film enthusiasts, students, and scholars to explore Elam’s films today.

JoAnn Elam in Boyers and Rhinos (1981).