By Aurore Spiers, University of Chicago

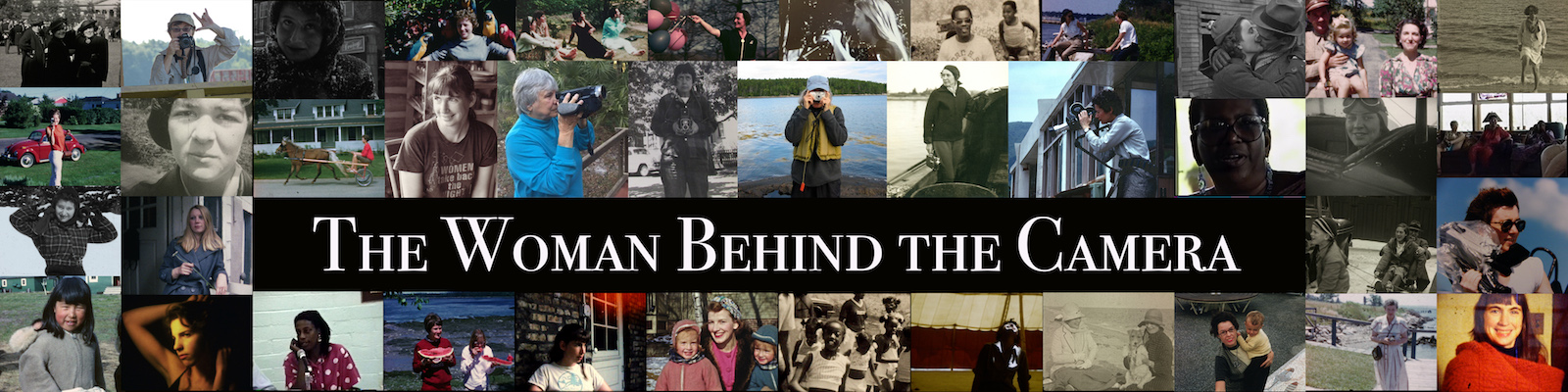

JoAnn Elam in the 1970s.

The JoAnn Elam Collection (1967-1990) at Chicago Film Archives (CFA) consists of approximately 735 film, video, audio elements and some paper material, which JoAnn Elam’s husband Joe Hendrix donated in 2011. In addition to Elam’s best known films, such as Rape (1975) and Lie Back and Enjoy It (1982), the collection includes dozens of short films and home movies as well as footage and audio tapes for some unfinished projects like Everyday People (1978-1990). Diaries, notebooks, research material, scrapbooks, and production notes for Everyday People complete CFA’s collection, which gives us unprecedented access to Elam’s rich body of work.

JoAnn Elam’s Notebooks, ca. 1977-1983.

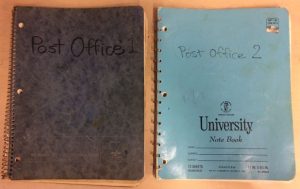

Page from JoAnn Elam’s Notebook “Post Office 1,” ca. 1977-1978.

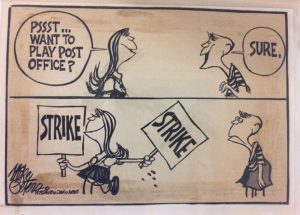

As I began working on the JoAnn Elam Collection last summer, I became interested in Everyday People, one of Elam’s most personal films that remained unfinished at the time of her death in 2009. According to her diaries and notebooks, she started filming her colleagues from the Logan Square post office in Chicago in late 1977, a few years after she was hired there as a letter carrier. In 1978, Elam wrote about the “post office movie” she wished to make: “It’s about delivering the mail, day-to-day, rather than specific events (1978 strike). Strike, work rules, management harassment, relationship to public. Other issues are brought in as they affect day-to-day.”

Following a decade of major strikes leading to the Postal Reorganization Act of 1970, the newly created United States Postal Service (USPS) implemented a series of measures to modernize its facilities and mechanize the sorting of the mail. Several titles from the JoAnn Elam Collection document this moment in the history of the American post office, when tense negotiations between the administration and the postal workers’ unions led to more protests and strikes, and, in some cases, victories for the workers. At least three times between 1978 and 1982, Elam served as one of Chicago’s union delegates to the National Association of Letter Carriers biennial convention. Elam’s “post office movie,” which she renamed “Everyday People” around 1980, would focus on how these events and issues impacted the letter carriers’ work every day.

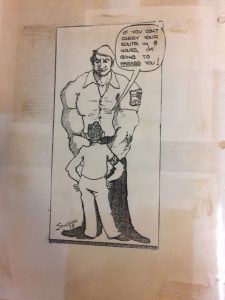

Cartoon from JoAnn Elam’s Scrapbook, date unknown: “If you don’t carry your route in 8 hours, I’m going to HARASS you!”

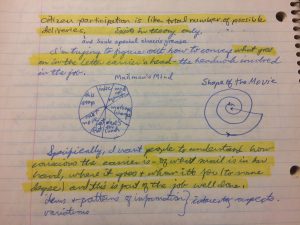

Still from Everyday People (1978-1990).

The version of Everyday People available for streaming on CFA’s website is the most complete rough cut found on a VHS tape (date unknown). This 22-minute version was shot on 16mm and video, in black and white and color, and probably with the help of several friends, including Chuck Kleinhans from Jump Cut. It includes footage and audio interviews of Elam’s colleagues at the post office from the 1970s and 1980s, with and without titles. Elam’s personal diaries and notebooks from 1977 through 1983 and her production notes from the late 1980s help us better understand Elam’s project, her hesitations, the political views she wanted to convey, and the structure and formal devices she intended to use. Together with the rough cut, this extra-filmic material offers a glimpse into Elam’s creative process, from the conceptualization to the editing of Everyday People.

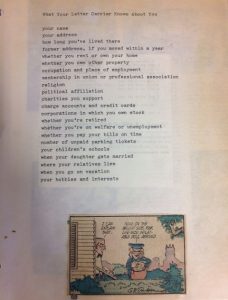

Page from JoAnn Elam’s Scrapbook, date unknown: “What Your Letter Carrier Knows About You.”

The film Elam envisioned was ambitious. In about one hour, Everyday People would describe what the work of delivering mail consisted of, how it was fulfilling to the mailmen and women of the USPS, how the events mentioned above affected them, and how they could become good letter carriers. In Elam’s words, the film’s objectives were: “1) to show people who have no awareness other than getting their mail what it’s like for the people who deliver it—to show what work involves; 2) to show some of the basic fulfilling aspects of work—competence (doing it right), relevance (structured relationships with people), exertion, discipline; 3) to analyze the way the post office operates—how and why things are done, and how mail delivery and the carrier’s work are affected; 4) to make letter carriers more aware of what their job is and how I think it should be done. More specifically, to encourage and reinforce a particular attitude toward the work, the people, and management. How to be a good carrier.” The film would include images of letter carriers delivering the mail and interviews, thus achieving its four objectives visually and formally, through sound and editing. The intended audiences included experienced and new letter carriers as well as the general public, the receivers and senders of mail.

What Elam called her “ongoing What-Kind-Of-A-Movie-Is-This? Struggle” was certainly one of the reasons why the film remained unfinished. For instance, on September 23, 1978, Elam wrote to herself: “Keep in mind the movie is really about The Mail (The Mail is an endless mystery) and the Postal Service (the Post Office is an endless folly) and The Weather (Everybody Talks about The Weather and nobody does anything about it), and Conditions of Employment.” A few weeks later, on December 16, 1978, she kept wondering: “What is my relationship to my material? Is it the mailmen or the mail? It’s The Work.” On February 4, 1979, Elam expressed that, “there are several specific things I want to get across, like that people should put their name on their mailbox, put apartment numbers on letters, etc. Other than that, I would like them to understand that some mailmen (many) are proud of doing a good job and are involved in their work. What I want to convey about the work itself is the nature of it (what we do), the material of it—mail, equipment, clothing, mailboxes; the combination of repetition and variation, the attitudes that the role creates, toward the physical surroundings, people, ourselves.” At times, these practical considerations gave way to fantasy, as when Elam mentioned “the ideals. How it [the USPS] should be,” briefly renaming Everyday People “the Fantasy Post Office.” Always on Elam’s mind, however, was to pay tribute to the hard-working letter carriers delivering mail year round, often subjected to harassment, racism, and sexism from management, and undervalued in American society.

Reaching the American public was crucial to Elam’s project, even if the film’s multiple modes of address proved extremely difficult and probably delayed the production further. Although Elam’s notes are unclear, she might have wanted to use sound as a counterpoint to the images, with the “sound message” addressed to the “general audience” and the images to the letter carriers, who would “pick up on subtle messages, unconnected but not conflicting with sound message.” Elam’s film would continue experimenting with sound, images, and titles in a similar way to Rape, where the titles sometimes repeat or add to the women’s testimonies about sexual abuse. But compared to Rape, Elam said, “Post Office will have more variation and conscious pacing. Sections will be broken up by commercials. Sound and picture will develop in parallel (…). Little if any lip synch.”

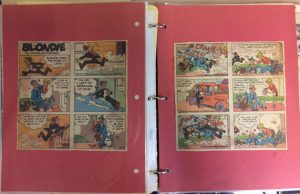

Pages from JoAnn Elam’s Scrapbook, date unknown.

Cartoon from JoAnn Elam’s Scrapbook, date unknown.

Unfortunately, Elam does not say what commercials she wanted to include and whether those would speak to her “general audience” and/or the postal workers. Still, this reveals Elam’s interest in the way mailmen and women were represented in the media, as her scrapbook of newspaper clippings further evidence. Letters from 1984 to various record companies also indicate that Elam tried to acquire the rights to several popular songs, such as Sly and the Family Stone’s “Everyday People,” Elvis Presley’s “Return to Sender,” and The Marvelettes’ “Please Mr. Postman.” Put in dialogue with the voices of mailmen and women, the commercials and songs would show the social value of postal workers to themselves and to the communities they serve in a profound yet whimsical way.

The extant version of Everyday People from CFA’s collection accomplishes some of these ideas about structure and editing. It starts with sequences showing Nancy Morgan, Juan Ortiz, Joe Hendrix, and Joan Davis delivering mail. As men of color and women, Elam’s four colleagues stand for U.S. Post Office’s diverse workforce. Superimposed yet not synchronized onto this footage, their voices speak of the racial and social diversity and of the opportunities offered to women and African Americans at the USPS. A series of more rapidly edited shots of Morgan, Ortiz, Hendrix, Davis, Elam, and other letter carriers going in and out of buildings follows. Hendrix, Davis, Morgan, and Ortiz (in this order) then talk about their relationship with the communities, their responsibilities, and the difficulties they encounter on the job over footage of them on their rounds. During these two montage sequences, two songs titled “I am a Happy Mailman” and “Watch that dog” (using the melody of “Jingle Bells”) also present their work as gratifying even if demanding. We next see various workers sort the mail at the post office, carry it into trucks, and deliver it, along with archival footage of postal workers from the early twentieth century. Even if this version of Everyday People ends abruptly, with Hendrix stating that these “old days are gone,” it is probably close to what Elam had planned in that it documents the labor required for the American people to receive bills, paychecks, personal letters, and packages every day.

The relation between sound and image that Elam struggled to conceptualize makes her vision of the post office most manifest in the rough cut. While the images convey the repetitive and mechanical nature of the work, the voices of the four postal workers offer a more complex account destined to the general public. Against common ideas about the postal workers’ incompetence and laziness, Everyday People insists on their courage and dedication.

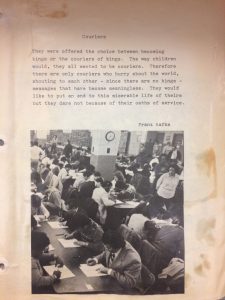

Page from JoAnn Elam’s Scrapbook, date unknown: “Couriers” by Franz Kafka.

Significantly, Elam’s production notes indicate that Franz Kafka’s “Couriers” was to be used during the closing credits. Kafka wrote that couriers “were offered the choice between becoming kings or the couriers of kings. The way children would, they all wanted to be couriers. Therefore there are only couriers who hurry about the world, shouting to each other—since there are no kings—messages that have become meaningless. They would like to put an end to this miserable life of theirs but they dare not because of their oaths of service.” In Everyday People, Kafka’s world without kings is the USPS, where the growing mechanization and the use of computers has led to the devaluation of human labor. Despite the repetitive nature of their work, Elam explains, letter carriers are not robots, but valuable workers that the general public should support in their fight for decent work conditions.

As a work in progress, Everyday People presents a challenge to film scholars interested in JoAnn Elam. Over a period of at least ten years, Elam changed her goals, the structure of the project, and the material she wished to include several times. She apparently showed versions of the film to some of her friends from Chicago’s experimental film community and to her colleagues from the post office, whose feedback she valued immensely. Traces of her long search for the right aesthetic are everywhere in her diaries, notebooks, and scrapbooks, but the personal nature of these documents often make them obscure to the unintended readers that we are today. Still, Everyday People has shown me the merits of incomplete film works. Because they often reveal so much about their creator’s filmmaking practice, they force us to search for new methods, which would consider film fragments, scraps of paper, and discarded ideas on the same level as more definitive elements. The work of Chicago Film Archives on the JoAnn Elam Collection gives us a place to start.