The following is adapted from a short presentation given by Brian Belak, Collections Manager for Chicago Film Archives, at the Association of Moving Image Archivists’ Annual Conference in New Orleans, LA, on December 1, 2017. The panel “Woman Behind the Camera: Uncovering An Overlooked Perspective” also featured archivists from Northeast Historic Film, the Lesbian Home Movie Project, and the Center for Home Movies discussing their work on the project.

The JoAnn Elam Collection came to CFA in 2011 and consists of over 735 total elements, 516 of which are reels of 16mm, 8mm, and Super 8mm film, with the remainder videotapes, audiotapes, and several boxes of papers and fixed ephemera. Elam herself was a central figure in the Chicago experimental film scene of the 1970s and ‘80s. Her work is engaged with issues of feminism, depiction of women and women’s labor in media, and domestic and everyday spaces on film.

JoAnn Elam in “Boyers & Rhinos” (circa 1981)

Although Elam made significant work on 16mm, the majority of her films were made and shown on 8mm, which she argued made the filmmaking “immediate and personal.” As she wrote in a manifesto with her friend and collaborator Chuck Kleinhans, “Small gauge film is not larger than life, it’s part of life.”

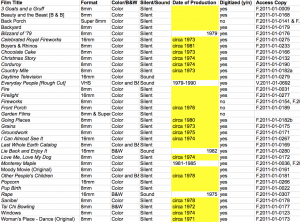

Before undertaking this project, our work with Elam’s films was mostly through attempts to build a filmography of finished films to put online. Elam passed away in 2009, and the collection was donated through her husband Joe Hendrix, her sister Susan Elam, and Chuck Kleinhans. From the beginning, we lacked access to Elam and were unable to ask her questions directly. This meant we needed to construct a filmography through research and the memories of her family and friends. This filmography included RAPE (1977) and LIE BACK AND ENJOY IT (1982), Elam’s two best-known works due to their ongoing distribution by Canyon Cinema. These two and a small number of other titles could be identified through clearly labeled printing elements, copies, or outtakes that point to finished works. Many films have printed title cards, and we also have copies of catalogs and screening notices that identify some films by title.

This led us to a working filmography of about 35 titles in 2014, the last time significant work was conducted on Elam’s films. Most of these titles were digitized and put online at that time, while the entire collection was also inspected and rehoused.

In 2017, we’ve taken up digitizing and understanding the remainder of Elam’s collection. A large portion of that are the elements for her unfinished film “Everyday People” about letter carriers in the US Postal Service, a role she held herself and through which was actively engaged in union work. But what has proven harder to make sense of is the significant number of reels without clear marking or identification. Some have simple labels, such as a person’s name or a location. Some have no labels at all. Many came to us in cracker boxes with broad labels like “Old Camera Rolls,” “Camera Rolls,” and “8mm Film.” There are spliced reels, uncut originals, printed elements, and loops.

“Humb,” which we believe is short for Humboldt Park in Chicago, is a great example of the sort of newly digitized material we find difficult to classify because in appearance, the film is engaged with the same themes and formal experimentation as the working filmography developed before, in which we saw techniques like double exposure and montage. However, the reel itself has an obscure, likely incomplete title, and there’s no record of her exhibiting the film to others.

Currently the catch-all “Finished Films, Home Movies, and Sketches” section of Elam’s finding aid consists of just one list of over 150 titles, combining the previous working filmography with newly digitized and streaming material. This is a daunting list for researchers that risks elevating certain unfinished or unintentional films to the same status as Elam’s finished and exhibited work.

Sorting through this material has caused us to question how best to subdivide and present the list in an understandable way mindful of Elam’s intent. One simple method could be to use their original box groupings, with the idea that those groupings may indicate meaningful relationships. However, this may separate related objects from each other, such as trims and outs for finished pieces, and break apart intellectual understanding of Elam’s recurring interests. Plus, it’s not guaranteed who grouped these films and if the labels came from Elam, her husband, Kleinhans, or someone else.

Another approach could mean grouping films based on their content, as we can see that Elam was interested in filming similar events or activities over time. Multiple reels depict her and others gardening, an annual art fair in her neighborhood, and visits to a farm in Monterey, Massachusetts, owned by her longtime friend Bonner McAllester. But this approach carries its own complications discerning works from related outtakes. Is a reel labeled “Fire” its own work, or outtakes for another film called “Firelight”? Were any of these related reels intended to be edited into larger pieces, and if so, what evidence survives?

“Firelight” (left) and “Fire” (right) – dates unknown. Elements of the same film or different altogether?

This last point brings up the issue of how to categorize Elam’s films more broadly. Since even her exhibited work is so engaged with the personal and everyday around her, and was mostly shot on consumer formats of 8mm and Super 8mm, how do we consider her films in relation to home movies in the collection? In the Small Gauge Manifesto, Elam and Kleinhans wrote that small gauge “invites films made for or with specific audiences. Often the filmmaker and/or people filmed are present at a screening.” This sounds like a traditional definition of home movies, blurring the distinction between Elam’s art practice and the seeming home movies apparent in the collection. It’s not always clear who shot these home movies, as Elam herself often appears in them in a casual setting. For many, it may have been her husband Joe Hendrix, but the authorship remains unclear. Hendrix has passed, and we are unable to ask him, though Elam’s sister Susan has confirmed that there is a series of films in the collection made by her on a trip to Europe.

The Small Gauge Manifesto also asks us to consider the ways in which we put these films online for anyone in the world to access. Although our computer screens are still smaller than a movie screen, keeping in line with that vision of small gauge on a small screen, there is also the change in the environment of presentation. Elam is not with us as we watch her films online. Most of the time we are not intimately familiar with those featured in the work. Since online presentation therefore requires a translation of Elam and Kleinhans’ vision of personal filmmaking, the challenge becomes how best to acknowledge the translation and contextualize their vision for future audiences engaging with the films.