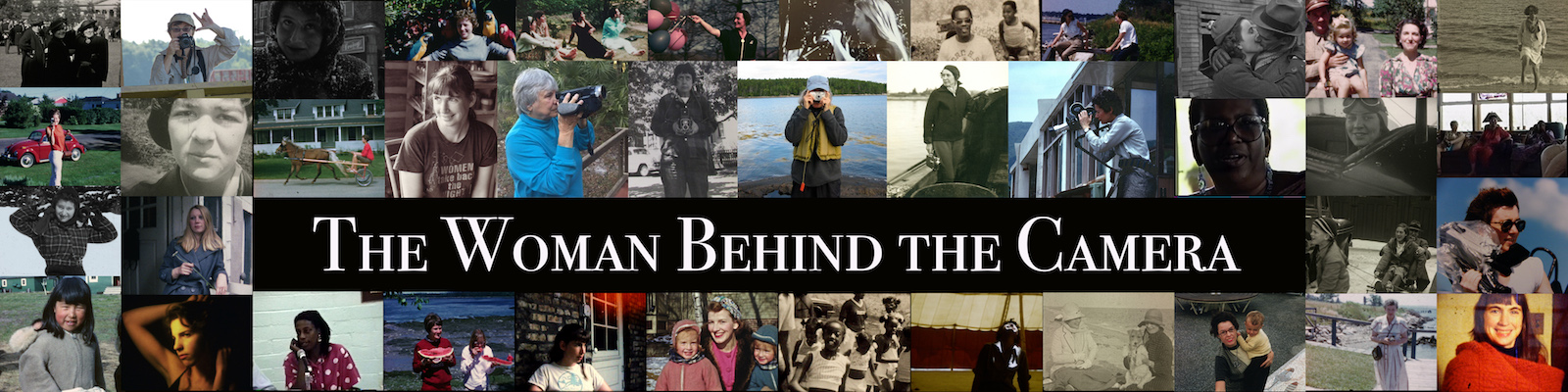

By Sharon Thompson, Executive Director, Lesbian Home Movie Project

Lesbian Home Movie Project (LHMP) is nosy. We won’t take footage unless the possessor agrees to help us document it. And we don’t just ask for the meat and potatoes of moving-image archives, dates and locations. We ask what was happening when the footage was captured. Who loved whom on that softball team? What is that one whispering? What did that bear hug signify? That wink? That kiss? Who’s still alive? Why the footage on that particular garden? That bridge?

“Shadblow Tree,” Ruth Storm Collection, Reel 13, Lesbian Home Movie Project from Sharon Thompson on Vimeo.

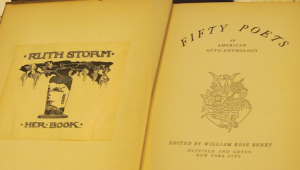

Ruth Storm (1888-1981), the lesbian schoolteacher whose work led to our project, created her longer reels by splicing. Those edited reels — Maine I, Maine II, Maine III, and New York — have been the focus of most of our research on her work and circles. We have talked to her last remaining friends. We have talked to their daughters. We have literally read her lips. (“You’re beautiful,” she tenderly whispers to a fawn in one frame.) But her collection also includes miscellaneous footage. On one 16mm can, she scrawled “Shadbush Tree.” One shadbush tree is all that appears on the reel. It bounces a little in a breeze. Hard to date and place but we’re still hoping. We even have a clue: a poetry book Ruth inscribed to a lover, now in the possession of that lover’s daughter. Could it possibly include this line from William Cullen Bryant: “the shad-bush, white with flowers, brightened the glen”?

It bounces a little in a breeze. Hard to date and place but we’re still hoping. We even have a clue: a poetry book Ruth inscribed to a lover, now in the possession of that lover’s daughter. Could it possibly include this line from William Cullen Bryant: “the shad-bush, white with flowers, brightened the glen”?

To a degree, this emphasis on unearthing intimate details is a personal tic. But there is a scholarly point. Detailed recollections are the stuff of social history. Queer histories of every sort have been assembled out of remnants, the torn letters, the yellowed journals, the audio tapes, the police records, of those who lived before us. Given how little intimate knowledge was intended to be preserved, social historians to date have done an amazing job of reconstructing those lives, sexualities, perceptions, and experiences out of these precious shreds. Linking home and amateur movies and tapes to extensive testimony and textual evidence, as The Woman Behind the Camera project does, will enable tomorrow’s lgbtq and feminist historians to take this work even further.

One key to the Lesbian Home Movie Project’s success in collecting closely held personal material has been our willingness to hold the private close. Frequently footage donors have had second thoughts after we have enabled them to see their footage again, often for the first time in many years. The pain of a lost relationship may be reignited or the fear that led an elder donor to hide a passion in her closet for many years. Elder donors also often impute sensitivities to people they’d half forgotten. One woman I hoped to interview called in the wee hours to excoriate me for proposing to screen a lesbian wedding ceremony that took place decades before gay marriage was a legal possibility. The parties involved had split up soon after the occasion, she announced. Even mentioning that they had once loved each other so much that they ceremonialized their love would be terribly embarrassing. And no she wouldn’t ask them what they actually felt. That would be horribly improper. And no she wouldn’t give their names or offer any clues to contacting them and asking their actual opinions. And no she would never change her mind. Moreover, I was the most horrible person she ever heard of for refusing to destroy the evidence we held. If I were not the kind of person who would destroy it, I was not the kind of person to be trusted with contact information.

The fact that I’m telling this story reveals the extent to which she was right. I cannot be trusted to destroy evidence, especially not of the erotic or romantic variety. I want secrets to come out. I believe in testimony. That’s why I love archives even more than memory: their written documents, their oh-so-moving images. At the same time, I am the kind of person — much more importantly, this is the kind of project — to be trusted with secrets for the present.

Because confidentiality is as much a hallmark of Lesbian Home Movie Project as curiosity, we (our board of three, Kate Horsfield, B. Ruby Rich and I) anticipated that the emphasis of the Council on Libraries and Information Resources Hidden Collections grant on streaming footage might damage more than abet our work and insisted that we would not stream what we were asked not to stream and would make every possible effort to locate the people in front of the camera and obtain their permission to stream or include their names in a finding aid or viewing log. If a piece of footage were already up and someone in it emerged and objected, we would take it down immediately. If it weren’t up yet but just on the list, we would cross it out. Still we feared that bringing so much footage out of our closet might impede future donors from coming forward. That may be happening to a degree. But the project has also proven a lure. We’ve recently accepted two new collections — one large, almost seventy items, one just four short, delicious Super 8 reels. Both seem to have come in partly because the filmmakers appreciated the concept of the project and the idea of their work becoming accessible and a part of history. Dealing with these collections has added extra time pressure to meeting the grant terms. But it is also enriching the project itself and will greatly enlarge the portrait that ultimately emerges of women behind the camera and their partners in crime and art and history, the subjects in front of it, as well as the last near one hundred years of lesbian amateur filmmaking, the movements and the private lives that led to where we are now: a place and time in which more and more women define the boundaries of their work, and share cinematic assertions that include but also aim beyond the domestic, the personal, and the secret.