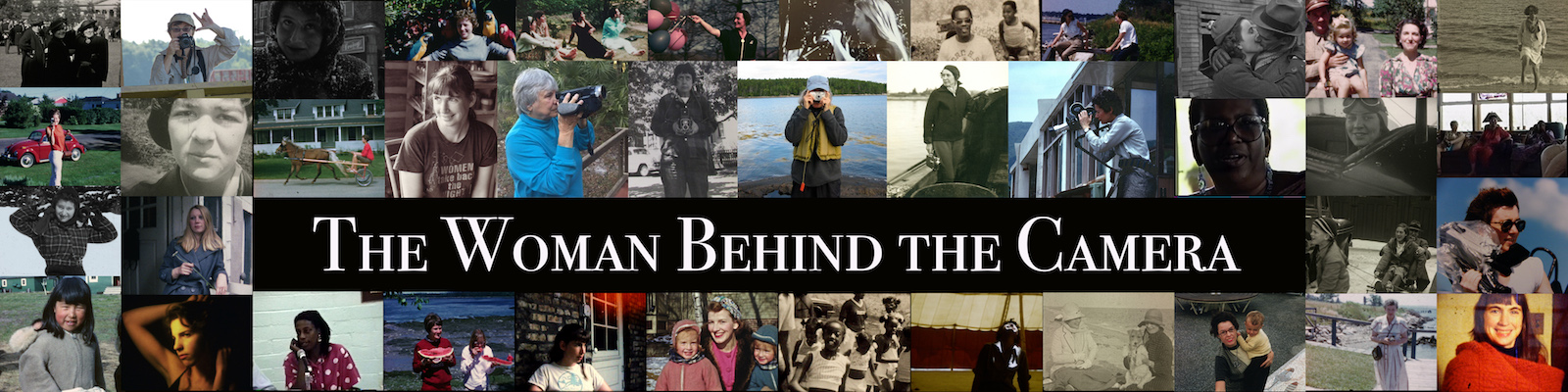

Millie Goldsholl’s Rebellion of the Flowers (1992) appears to be the last film she completed and one that she poured an incredible amount of creative passion and energy into. Completed three years before her husband’s death, the film is dedicated to “Morton Goldsholl and the Good People who resist the abuse of power in any form.” It’s easy to see Millie’s love and admiration for her husband reflected in the content of the film—in particular its emphasis on respect, humility, and equality.

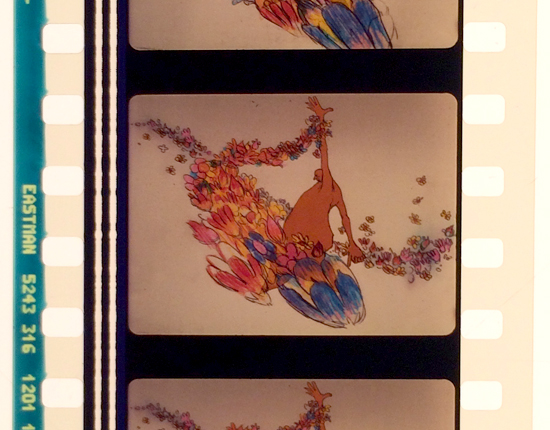

Narrated by Shepard Strudwick, Rebellion of the Flowers tells the story of a gardener, Jan, who “understood nature’s needs” and worked hard to grow and care for his plants. He protected and looked after his flowers, providing them with “love and gentle care.” He took great pride in his work and, as a result of his labor, felt “filled with purpose” and “close to God.” However, Jan’s love and adoration of the flowers transforms into a distortion of his power, as he becomes jealous of the flowers bowing “under the intense authority of the sun.” Jan’s body reflects this internal transformation, and he becomes a looming totalitarian figure demanding the obedience of his flowers.

When he realizes that his shadow can block the sun, the flowers rebel and twist around his body, drawing him into the earth. The next morning, the sun comes out, and a “sparking and sweet smell” (perhaps Jan’s body transformed into metaphorical fertilizer) mixes with the natural perfume of the flowers.

Rebellion of the Flowers is an uncommon instance in CFA’s collections in that the Goldsholl Collection also holds a wealth of film material associated with its creation. Beyond a few finished positive prints, the collection contains edited negatives, negative trims, internegatives, interpositives, work prints, and magnetic soundtrack reels. While the positive prints are the most immediately useful for actually being able to watch the film, these elements are also important to preserving the work in its entirety and understanding how the project developed for Millie over time.

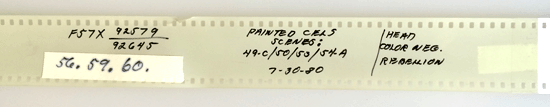

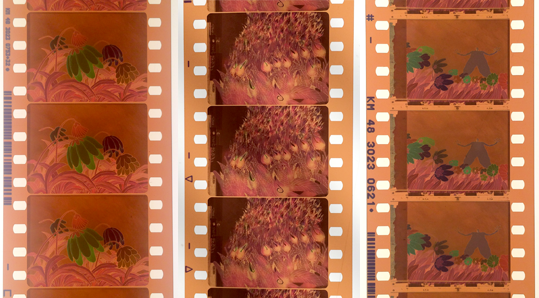

Most of the film elements are either labeled or on film stock dated 1991 or 1992, when the film was completed. Even so, we’re able to trace through the film stocks of other elements that Millie actually started work on the film at least ten years before then. One negative trim is dated to 7-30-80, while in a work print labeled “1992-06-12, re-edited by Millie,” there are sections of the film printed onto film stock dating to 1985 and even 1981. The 1981 stock in particular dates to before the Eastman LPP “no-fade” stock used for all other more recent elements of the film, meaning the 1981 portions have all nearly completely faded to magenta, while the remainder of the work print has held its color well.

The dates on the work print corroborate a comment made in a 1994 review of the Tenth Annual Chicago International Children’s Film Festival written for ASIFA Central, the Midwest USA Chapter of ASIFA (l’Association Internationale du Film d’Animation), of which Millie was a member. Referring to the Chicago premiere of “Millie Goldsholl’s long awaited ‘Rebellion of the Flowers’” suggests there had been news of its production for years prior.

The various elements offer a record of how the film was made, not just when. For the most part, the negatives were exposed through a gate larger than the final print, so there are notes or extra imagery on the edges that were cropped off when making the positive version. The many layers of hand-drawn cel animation were kept in registration by pins at the top or side of the sheets, which get preserved on a few of the negatives. For some of the close-ups on flowers in the film, the negatives show images with the scientific names of the flowers written beside them. There are also color test cards, leader ladies, slates specifying the negative roll, and plenty of grease pencil markings throughout as editing took place and changes made.

For now, we chose one positive print labeled “virgin release print” to scan and prepare for digital exhibition, while the other elements were cleaned, repaired, and rehoused for storage and future research. This is all without having an opportunity to transfer the full-coat magnetic sound reels, which may contain additional audio beyond what’s heard in the film, such as outtakes or spontaneous noise captured during recording.

Perhaps because the film took over 10 years to complete and was worked on by a relatively large team of animators (including Ken Mundie, Paul Jessel, Marie Cenkner, Dan Chessher, Mary Jones, and John Weber), its style is quite different than other films made by Millie and the film division at Goldsholl Associates. Drawn illustrations of the flowers and natural world are contrasted with the domineering and almost grotesque figure of Jan. Images of flower petals delicately unfolding are animated with extreme sensitivity. Superimpositions and slow cross-dissolves are used to evoke a sense of fluidity within the natural world.

Rebellion of the Flowers’ critique of power and authority resonates with another award-winning hand-drawn animation created by Millie Goldsholl, Up is Down (1969), that tells the story of a boy who sees the world differently than others and, as a result, is considered a threat to society. Efforts to transform the boy’s positive and hopeful worldview are unsuccessful, and he revolts by asking society to reevaluate its values. Dedicated to Martin Luther King, Jr., the film reflects an emphasis on political and social consciousness that can be seen in the Goldsholl studio’s progressive attitude and early emphasis on gender and racial equality in their hiring practices.